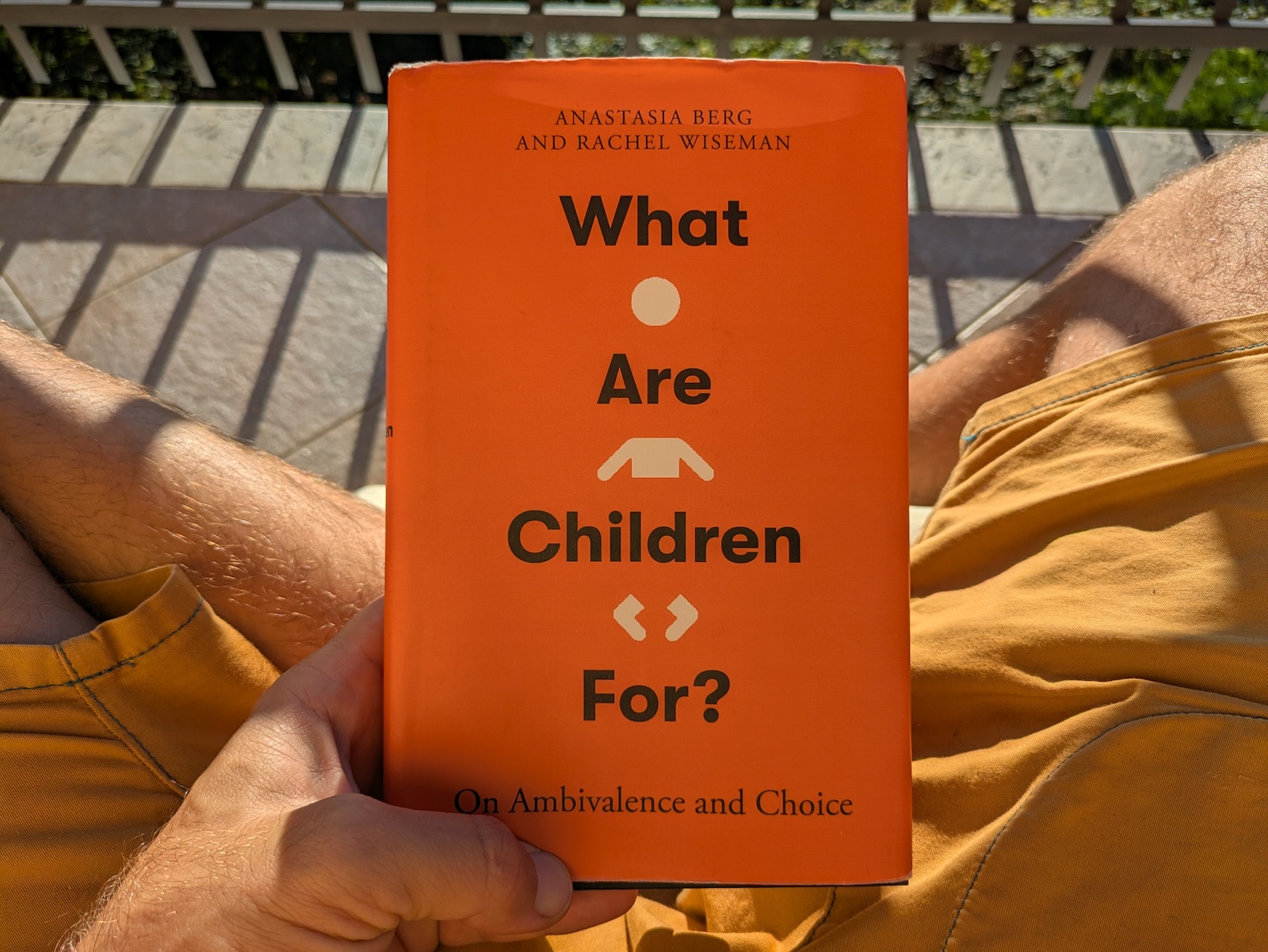

I just finished reading this dense, excruciatingly philosophical, and occasionally brilliant book.

It’s one part sociology, one part memoir, and one part feminist literature review, topped with a heavy dollop of climate anxiety.

I wouldn’t recommend this for a general audience—it’s written by, and for, high-flying literary types—but I’ll happily share some quotes. Bold indicates my favorite lines.

(See also: Conflicted Thoughts About Having Kids and my favorite quotes from Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed)

ON PARENTING AS “THROWING YOURSELF OFF A CLIFF”

Becoming a parent, for those of us on the outside, can seem less like a transition and more like throwing yourself off a cliff. When my friends and I talked about the prospect of having children, we spoke about it with casual detachment, as if conducting a thought experiment populated by people who were not us but total strangers. Well into our early thirties, when the conversation veered closer to our lives as we were actually living them, we retreated to a familiar place of uncertainty: I dunno, maybe one day, I guess, it depends, we’ll see. No matter how demanding, all our attachments—to our one-bedroom apartments, our midlevel jobs, our romantic partners—felt tenuous and temporary. Adding a child into the mix was practically unthinkable. Something about parenthood seemed inimical to my existence; I suspected it would change me so much that I’d become unrecognizable to myself. I worried that everything I enjoyed or that made me a halfway interesting person would recede beyond my reach, that I’d never be able to finish a book again. We all said that if we had kids we would “somehow make it work,” but no one really believed the halfhearted propaganda. How do you figure out how to throw yourself off a cliff?

ON CHILDREN AS A CHOICE, NOT AN ASSUMPTION

Certainly, childlessness is hardly a contemporary phenomenon. But to be childless was often understood to be a misfortune, or a sacrifice—at any rate, a state of exception that usually involved a form of radical compromise or renunciation. That at some point in life one would start a family of one’s own was, for the most part, as inevitable as growing older. That one would bring forth life, or at least try to, was just about as certain as death. Like moving out of your parents’ house and getting a job today, having children was just what people did, not something one had to weigh against a sea of other options. Like sleep, children were something one had to work around while pursuing other goals. Under those conditions, it made little difference that one might die in childbirth, that one might not be able to provide for one’s family, that one’s children might suffer, that they might die young. And it certainly made very little difference that one had other hopes, such as traveling or advancing in one’s career.

Today, by contrast, for many people, having and raising children is no longer understood as a necessary part of a full human life. Having children is but another possible project, with its own attendant emotional experiences, social obligations, and financial responsibilities. According to a September 2023 Pew Research report, only 26 percent of Americans today say having children is important for living a fulfilling life, whereas 71 percent consider “having a job or career they enjoy” to be essential, and 61 percent say the same for “having close friends.” . . . When children are seen in this light, it’s understandable that many people, certainly those whose lives feel uncertain and precarious, dread giving up their time, energy, resources, highest ambitions, and—perhaps above all—freedom to the task of raising another human being. When you compare having children—a resource-guzzling enterprise that comes with no guarantee of mental or material satisfaction—to all those other possible attractive ends, how could it ever measure up?

ON THE PERILS OF “SLOW LOVE”

…even for those who think they might want to have kids, the exhortation to “find” or “fulfill” themselves before deciding how family will fit into their life can encourage indefinite waiting. The thought of starting a family remains suspended, something you’re meant to get to eventually, once you’ve checked off enough of your personal and professional to-dos: a degree, a satisfying and well-paid job, a few key accomplishments, a vital social life, sorting out your issues in therapy. But at the same time, the indeterminacy of the standard of readiness can make it difficult to know when you’ve reached it, contributing to an ongoing, and often paralyzing, cycle of introspection and self-doubt. [. . .]

Dating and finances are stressful, and at a time when so much in the world feels perilous and uncertain, proceeding with caution is sensible. The logic of patient sequencing, at work and in love, is so compelling, its norms so pervasive, that it can sometimes seem like there is no viable alternative. Throwing caution to the wind and running off with the next stranger you meet on Hinge sounds hardly more promising. But the opposite of caution is not necessarily naïveté or blindness. We should remain open to questioning the prudence of delay. Professionally, the more established you are in your career, the more of a hit it might take when you finally decide to have kids; romantically, slow love might push the question of family off until it’s no longer an option. One thing seems right no matter what your actual goals are or come to be: it is good to start asking the important questions early—early enough to ensure that the future is not decided for you. That’s what it really means to be in control.

ON THE FEMINISM OF SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR (“THE SECOND SEX”)

For Beauvoir, to be truly free meant achieving “transcendence”—that is, rising above the biological, familial, social, and political conditions into which you were born and paving a path for yourself of your own accord. Free human beings are not simply defined by their past or present circumstances but are capable of determining themselves and their lives with a view to an open-ended future and its untold possibilities. This is hard for any human being to achieve, but for a woman especially so. The reason? Motherhood: the fact that women are the involuntary seats of biological and social reproduction. “From puberty to menopause she is the principal site of a story that takes place in her and does not concern her personally.” The capacity to mother is women’s greatest obstacle to attaining an authentic form of life.

ON THE FEMINISM OF SHULAMITH FIRESTONE (“THE DIALECTIC OF SEX”)

Firestone argued that the role of biological sex must not simply be rethought but overcome—totally and unconditionally. Dedicating The Dialectic of Sex “to Simone de Beauvoir, who endured,” Firestone found one serious failing in her intellectual forebear: while Beauvoir vividly captured the myriad restrictions and indignities meted out on women, in her analysis of the grounds for the inequality of the sexes she relied far too heavily on abstract philosophical categories like “transcendence” (or “immanence,” or “the Other”). Firestone thought there was a far simpler explanation for inequality: it “sprang from the sexual division itself.” For Firestone, the very fact that we divide humanity into “men” and “women” based on their differing roles in reproduction necessarily produced inequality. It was a matter of “biological reality” that the traditional family was based on “an inherently unequal power distribution,” and, as a consequence, it would remain inegalitarian and unjust as long as it existed.

The hard truth, Firestone contended, is that the mutual dependence of mother and child—and, in turn, their dependence on men—is inescapable. Children are always helpless and require monitoring and care, and it is women who must bring them into the world. Women, Firestone observed, are necessarily “at the continual mercy of their biology” for the better portion of their lives. Stuck in a cycle of pregnancy, labor, breastfeeding, and childcare, women remain reliant on men for sustenance and protection. These fundamental realities result in a division of labor within the home, any home, that is the root of inequality in all societies around the world. The problem, Firestone insisted, was not that men were not doing their share or that patriarchy, heterosexuality, and monogamy have restricted the horizons of women; as long as humankind seeks to reproduce itself “naturally”—that is, through the bodies and labor of women—inequality will persist. To remedy the situation would require nothing short of eliminating the sex distinction as such. . . . With continuing scientific advances, she argued, we could divorce reproduction from women’s bodies altogether. In her speculative vision of the future, machines gestate fetuses and nurture babies until they’re no longer completely defenseless, women and children are endowed with full personal autonomy, the gender divide falls apart, and full “cybernetic communism” reigns.

ON MEN AS MOTHERS, PART ONE

While [Mary] Daly remained suspicious of males—particularly professionals like therapists and gynecologists—who tried to assume motherly roles, Ruddick maintained that the maternal orientation toward the world was a social identity that could, and should, be universally adopted. Ruddick defined a mother as any “person who takes on responsibility for children’s lives and for whom providing child care is a significant part of her or his working life.” Regardless of one’s capacity to physically bear children, and indeed, regardless of sex or physicality altogether, Ruddick believed that everyone should think and live “maternally.” Following the logic to its conclusion, she advocated for relabeling all men who take equal part in childcare as “mothers.” The revolutionary potential of such a reorganization of values was, according to Ruddick, nearly limitless, stretching far beyond the reconstitution of traditional gender roles all the way to a new, more peaceful, global world order.

ON MEN AS MOTHERS, PART TWO

Here [bell] hooks was echoing ideas found earlier in [Adrienne] Rich, who argued that men ought to be recruited en masse into a comprehensive childcare system in order to overhaul the gendered socialization of boys and men. For both Rich and hooks, this equitable redistribution of parental responsibilities was not the demand of some abstract ideal of fairness. Rather, it was necessary in order to change the expectations that children—both male and female—have of women and men, and thus to break down traditional gender roles in and outside the home. The effect on men, in particular, would be profound: as long as men do not learn to nurture—to care for children as well as for their fellow men and women—they will continue seeking out women to provide them with comfort, support, and acceptance. “In learning to give care to children,” Rich wrote, “men would have to cease being children.” Until then, men will continue to demand that women satisfy their every infantile need: a man “learns contempt for himself in states of suffering, and can reveal them only to women, whom he must then also hold in contempt, or resent for their knowledge of his weakness.” In a new world order in which men will not merely toy with fatherhood when it suits them but assume an equal share of the responsibilities of nurturing as a matter of course, both men and women will have “a greater chance of realizing that strength and vulnerability, toughness and expressiveness, nurturance and authority, are not opposites, not the sole inheritance of one sex or the other.”

ON BRINGING CHILDREN INTO A BROKEN WORLD

How can I, a prospective parent, bring a child into a world where I can never guarantee their basic safety and well-being, let alone happiness? Whatever the odds may be, the potential scope of human misfortune and tragedy can seem so great as to render any risk too high.

To see the problem with this final version of the challenge—and with the arguments from suffering more generally—let us suppose, for a moment, that it is right. Suppose, that is, that since no one, no matter how favored by chance, can guarantee that their child will not suffer catastrophically, all procreation is unjustified and therefore impermissible. A curious result follows. If it is wrong for anyone to bring a child into the world in the present, it has been wrong for everyone to have brought a child into the world in the past. In other words, every single human being—you, everyone you know or know of, everyone who has ever lived or will live in the future—was born out of a grave moral failure. It means that anyone who has voluntarily attempted, or just voluntarily risked, procreation has committed a serious moral offense. This is a conclusion that a philosopher like Benatar would happily embrace. And the very idea that an argument implies that many or most human beings have significantly morally erred is of course no objection to it—Aristotle thought ethical virtue was the share of the few, not the many, and Kant was happy to concede that perhaps no human being had ever done a truly morally worthy deed in their lives. The problem is that this argument implies something far more drastic: that the very possibility of human life—and with it, the very possibility of human action, which is to say, the very possibility of good and evil—turns out to be always predicated on a grave moral transgression. For anything good to have ever taken place, someone had to first commit a serious moral wrong. But here, we appear to have gone off the deep end. Starting with an understandable worry about the impossibility of guaranteeing the safety and happiness of our children, we’ve ended up on the verge of affirming that all human life is premised on a moral calamity. Could the basic fact of human vulnerability to the unpredictability of the future really render the reproduction of human life immoral? Is the reproduction of human life unjustified simply because we are neither omniscient nor omnipotent, that is to say, because we are finite beings, not divine?

ON THE GRITTY REALITY OF RAISING A YOUNG CHILD

[With a quote this long, I’m definitely pushing the bounds of acceptable citations—but it’s just so good! Go buy the book if you enjoy it. —Blake]

The first night we brought our baby back from the hospital, I saw a dark glimmer of what life would look like from then on, an inkling of the extent to which my hopes of carrying on as before—or better!—were absurd. “What have we done?” I heard myself weeping. “What have we done? Our life was good.” Sitting across from me, my husband said, “It’s a good thing that our life was good. It does not make more sense to have a baby when it isn’t.” He was right; but the more you have, the more you stand to lose. The more you like your life, the more often you might find yourself wondering what life would have looked like had you not had children. The older you are, the more confident and settled in your ways, the less you will appreciate having to change them.

When I try to convey what it has been like to raise our child, I hear an echo of David Wallace-Wells on the climate crisis: “It is, I promise, worse than you think.” Then I go blank. If it is difficult to express the purported joys of having children, it might be even harder to express the quotidian misery of it. I probably find this particularly hard because I used to believe that the inability to enjoy one’s child, wholly and completely, was a sign of personal failure. I recall vividly—the vividness due mostly to the embarrassment I now feel thinking about it—a friend of mine, who had a child a few years before I did, complaining that spending time with kids is very boring. How sad, I thought, that he did not love his own child as much as I would one day love my own. Did he not know how fascinating kids are? How much fun one could have playing with them? How fortunate one was to be let into their worlds of imagination and whimsy? [. . .]

About a year into raising our daughter, I was ready to admit defeat. I do not think I suffer from a lack of feeling toward her. I am affectionate, admiring, adoring. My responses to her are not affected or insincere. But hardly a moment is simple, unadulterated. Everything feels like an imposition on my time. After an extended period without childcare, even grading can feel like a form of self-care. “Boredom” is as good a name as any for the distinct irritation that I experienced for much of the time I had to spend with her. [. . .]

Pajamas off! Pajamas on! New socks, night socks, no socks. Yes hat, no hat, always hat, not that hat. Slippers on, slippers off, slippers in bed, slippers in bath, slippers to daycare, papa takes to daycare, mama takes to daycare, papa and mama take to day-care, NO DAYCARE. Bread, no bread, cheese, no cheese, milk in bottle, coffee in bottle, now we drink the bath water. No wipe. No bath. No hair. No nappy. Hug, hug, hug! Which sounds sweet but must never be delivered while her feet are on the floor: Up! Up! Up! [. . .]

Now, I am going to say something about sleep. It is almost as excruciatingly dull to listen to other people complain about how tired they are as it is to listen to them describe the technicalities and ethical quandaries surrounding sleep training. I will be mentioning neither and will keep it brief. Our daughter was and is an okay sleeper. It could be—as the forums, and blogs, and friends all assure me—much worse. She sleeps, we sleep, and that she sometimes wakes up too early for our comfort was not something we hadn’t been warned about. But for long stretches of time, getting her to fall asleep was hard, and the naps were not long. This sounds minor and prosaic. It is, very. In a sense, this is the problem. Getting a baby to sleep is a very prosaic thing, no intellectual or physical feat at all, and you have to perform it thousands, thousands, of times. You have to do it all day, every day, and no one can tell you, going in, how long the next attempt will take. I think back on how I felt reassured by the fact that little babies take four naps a day (a living, breathing Pomodoro timer!) and I can’t even muster a shrug. Imagine trying to get a teddy bear out with a metal claw four times a day, fifteen or twenty or thirty minutes at a time, suspecting the machine might be rigged, while the teddy was sobbing.

At one point, in our mercurial quest for “independent sleep” (place baby in bed, say goodnight, leave), we lost the ability to leave the room. For months, every evening we sat next to her, in the dark. A screen would have distracted her. So we just sat there, listening to her breathe. She demanded songs, but “not this one,” she babbled, she cried for whoever was not in the room. She asked for stuffed animals she was already holding. Adding up the hours, I’ve spent whole days—my husband, weeks—staring into the dark for unspecified and unpredictable periods of time, emerging into the living room squinting, irritated. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt simultaneously so overqualified and underqualified before. Once I sat for an hour watching her cry so hard she drooled and drooled and banged her head against the bars of her crib. (She was equally unhappy when I held her, and eventually fell asleep; she woke up, psychopath-like, perfectly content.)

Writing about the possible advantages of having children young, Elizabeth Bruenig assured those who still haven’t had children that doing so is “not the end of freedom as you know it but the beginning of a kind of liberty you can’t imagine.” I have a child and I still can’t quite imagine it. I have spent my entire life tracking excellence like a hound dog. Finding what I could do best has become a habit for me as much by temperament as by circumstance—my family life was so unstable, and the financial resources available to me so limited, that it became clear very early on that whether I would attain any measure of success beyond mere survival depended on my ability to excel. Excelling opened access to the scholarships I relied on for my education, which was in turn the basis of nearly every relationship and opportunity I have enjoyed since. The problem wasn’t that having a child kept me from excelling at my job. It didn’t help, but the real issue was that for most of my time spent with her, I wasn’t giving expression to any talent or ability whatsoever. I wasn’t growing, I wasn’t learning. So often I was barely doing anything at all.

This is the maddening paradox of parenting: it both had to be me and it absolutely didn’t. It had to be me: I wanted to offer my daughter the benefits of having a loving mother stably present in her life, there with her, attentively, day in and day out, deadlines permitting. But often it seemed like it really didn’t have to be me at all. Nothing about me—my ideas, my personality, my judgment, my sense of humor—really mattered. She wants her mother to sit next to her while she’s on the potty, or in the bath, or in bed, or in the car, but I’m at best just okay at sitting. She wants her mother to follow her on the playground, but I have no unique talent for the seesaw or pushing a child on a swing.

I’ve always considered myself to be rather whimsical, silly, playful, and I assumed that drawing on these qualities would render parenting a small child easy and pleasurable. I try to summon them as often as I can, but I did not consider how much time small children spend struggling to process discomfort, frustration, and disappointment; how much time I would have nothing to do but stand there and absorb a baby’s vociferous expressions of displeasure. It needed to be me, but a me not so much transformed as reduced to very basic functions. This is not what I think of when I think of freedom. [. . .]

Was this what they were asking about in asking me about motherhood? Were they asking not about a spontaneous transformation born of love and wonder but the necessary self-effacing that even a happy, funny, loving little girl mercilessly demanded her mother to perform in order to give her what she needed?

I imagine it will get easier, at least in some ways. She speaks in full sentences now, we’ve started playing games with rules and goals, I read her books I can’t memorize on the first go. One day, when I explain that we do not have something, or it is physically impossible for such a thing to exist, or it would be fatal for a child to possess it, the explanation will do something to mitigate the insistent demand for it. But now I understand something I would have absolutely refused to accept before: that when that day comes, when we can play sophisticated games, read longer books, conduct elaborate two-way conversations, I might still wish, at that very moment, that I were doing something else.